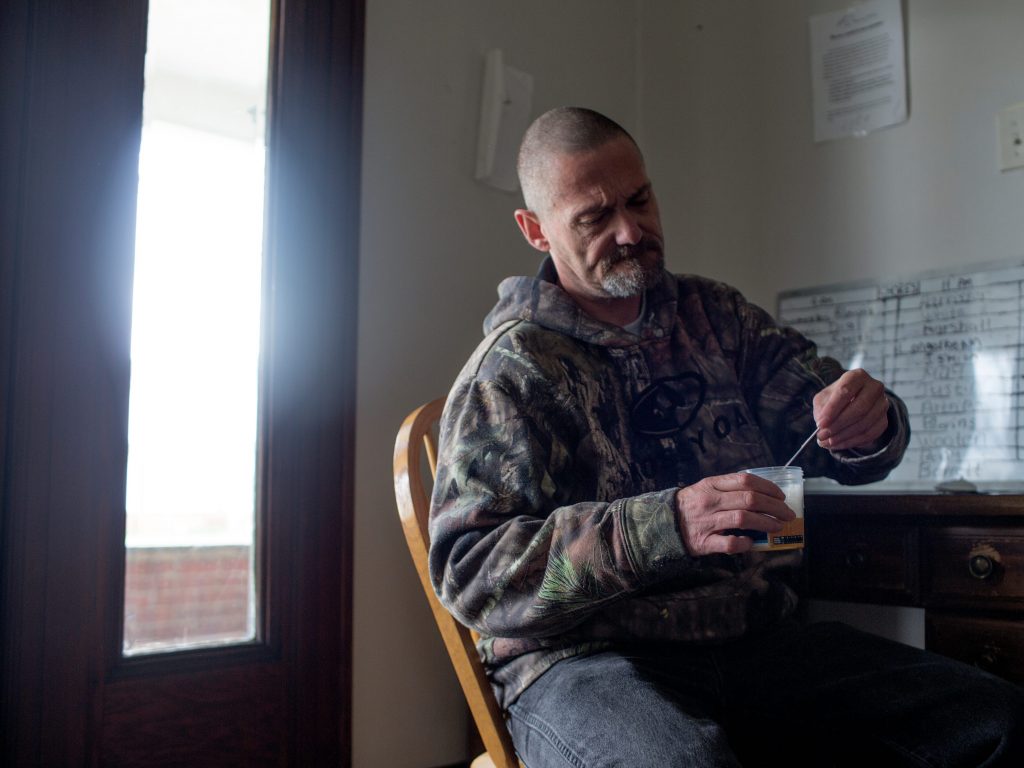

Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis/Getty Images

- Paul Constant is a writer at Civic Ventures and cohost of the "Pitchfork Economics" podcast.

- He and cohost David Goldstein recently spoke with journalist Sam Quinones about his new book on synthetic opiates.

- "Certain corporations behave like drug traffickers, and drug traffickers behave like corporations," said Quinones.

If you asked me to name the best journalists working in the country today, Sam Quinones would be in the top five. His meticulously researched book "Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic" helped draw attention to Purdue Pharma and the super-wealthy Sackler family's role in creating the opioid crisis that has overwhelmed America for most of the 21st century.

This week, Quinones released a new book that sounds the alarm on synthetic opiates, which potentially represent an even greater risk to America than the opioid crisis. Quinones joined David Goldstein and me on the "Pitchfork Economics" podcast to discuss that book, "The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth."

According to Quinones, the question of who profits from the spread of meth and synthetic opioids like fentanyl isn't as clear-cut as it was in his previous book. "Certainly there's an enormous population of people in Mexico that are profiting from it," he said. Producers get the chemicals to manufacture synthetic drugs from China and then they make the drugs in Mexico.

It's a synthetic-drug gold rush, "very much kind of a wild west," Quinones continued, with multiple competing drug-makers forcing the price of meth and fentanyl down in a ferocious competition. "It's like a constant glut economy down there right now," he said. "That's why you're seeing prices so low over the last few years, and why meth has come to areas that never ever had it all across the country."

Goldstein interjected to say that the system Quinones is describing "sounds to me like free market capitalism."

"That's absolutely what it is," Quinones confirmed. "The underworld is the most imitative, and at times the most innovative, fast-moving part of our economy."

When one producer found an affordable way to mix their drugs, for instance, everyone followed: "Pretty soon everybody is mixing these powders, one of which is extraordinarily deadly to human beings, in a Magic Bullet blender that you could buy for $29.95 at Target," Quinones said.

For the last five years, law enforcement officials have been raiding drug manufacturing facilities only to find production lines of dozens of Magic Bullet blenders bought at local Bed, Bath, and Beyond stores. The problem is, Quinones said, Magic Bullets "are uniformly bad at mixing powders, and that's why we got a lot of those cluster deaths early on," with nearly two hundred overdoses happening in a matter of days in places like Cincinnati and West Virginia.

"Absolutely, it's all part of unfettered, free market capitalism," Quinones said. "We live in a time when certain corporations behave like drug traffickers, and drug traffickers behave like corporations."

From sugary sodas to processed foods to social media and video games, "we are bombarded by legal addictive products from a whole array of corporations we can all probably name," Quinones said, and then illegal drug manufacturers are learning from those addictive behaviors and adapting their systems accordingly.

"Purdue and the Sacklers are small potatoes, almost, in this larger story of all these ways in which companies prod our brains to use their products, to buy them constantly," Quinones said.

In his book, Quinones offers a variety of reforms to the criminal justice system that in pilot programs have already shown great success in getting people off addictive substances and back into society. Keeping people struggling with addiction out of jail and in healthy rehabilitation programs is vital, as is establishing programs that help those who have already been imprisoned re-enter society on a positive footing.

But the first step, he says, is in acknowledging that addiction isn't a personal failure - it's a systemic one. That's why Quinones called his new book "The Least of Us." "We're all as vulnerable and as strong as the least of us - that grocery store clerk who may not have health insurance but still comes to work in the middle of a pandemic, who all of a sudden we discover is an essential worker but who doesn't have any safety net to speak of at all."